We were invited recently to contribute to an online event exploring how we can better help boys to be allies in the fight against male violence against women and girls. Here is a summary of some of the first part of what Susie presented on, in what was a really interesting event with a rich discussion.

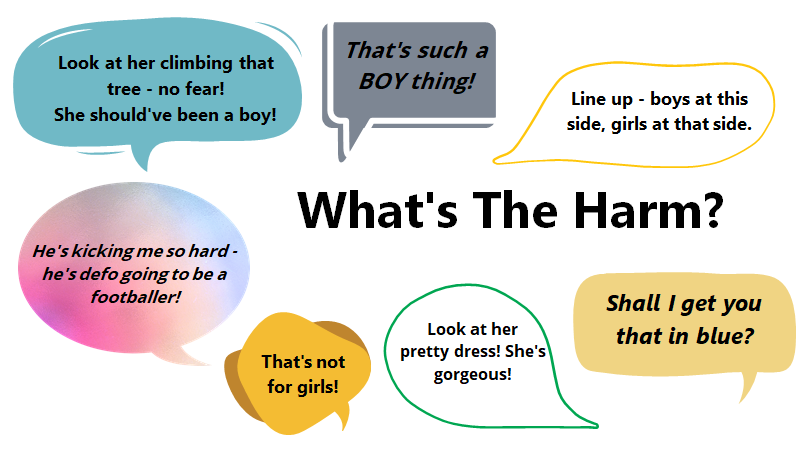

What’s the Harm?

As soon as we know the sex of a baby we begin to ascribe meaning, identity and expectations on the child based on their sex. These affect how we interact with a child, what we expect them to look like, act like, be able to do and achieve.

Ideas about masculinity and femininity are taught and reinforced by children, adults, by society, and by the media.

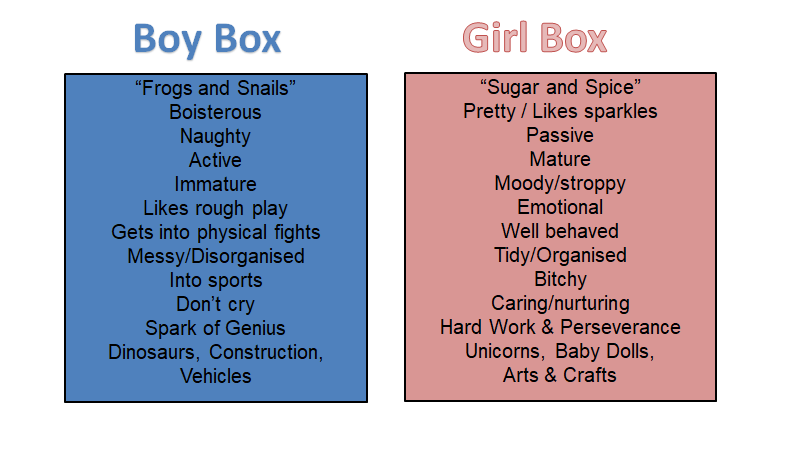

We begin to place children into two opposing boxes. These are gender stereotypes – children do not naturally fit into these binary boxes.

These stereotypes impact on how we as adults interact with children, and also how children interact with each other. In early childhood the behaviour and actions of boys in particular are policed more rigidly around these stereotypes – by society, and sadly by each other.

Boys and girls begin to see each other as different, as “the other” and we see a separation of the sexes.

By the time we are adults these gender boxes are firmly fixed. People face pressure to stay inside these boxes, and face repercussions when they don’t. These gender stereotypes have negative impacts on us all in different ways.

They feed many of the big issues that face us a society, including gender based violence, mental health, suicide rates, body image, eating disorders, homophobia and transphobia, the gender pay gap…the list goes on. These stereotypes harm everyone, and I believe it is in everyone’s best interests that we do whatever we can to combat them.

It is my belief that if we want to end violence against women and girls then we need to work on reducing gender inequality.

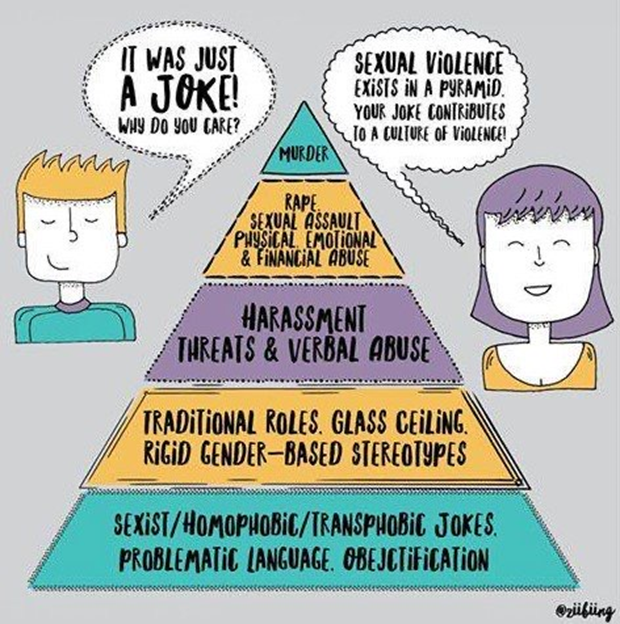

You may have seen this graphic before, or version of it.

The principle behind it is that if we ignore or turn a blind eye to the behaviours at the bottom of the pyramid, then we are creating a culture where people may feel emboldened or even permitted to progress up the pyramid towards more harmful, more violent and discriminatory behaviours.

If we want to prevent this violence, one way we can do this is to challenge and dismantle these stereotypes, sexism and sexists language which occurs at the bottom of the pyramid but contribute to a culture where women are seen to have less value than men.

This upholds the inequality which lies at the heart of men’s violence against women and girls.

“It’s only because he likes you!”

This might be a scenario familiar to you – A young girl approaches her care giver upset because a young boy has pulled her hair. I hope most of us wouldn’t respond in this way, but it’s not unheard of. On the surface it seems like quite a nice thing to say to calm her and make her feel better, but dig a little deeper and we can see some problems.

For a start this response frames the behaviour of young children in a heteronormative sexualised way. Children should understand that girls and boys can be just friends, that it doesn’t have to mean anything else.

It also teaches children that mean and aggressive behaviour is acceptable if you “like” someone. What is this saying to children about what they can expect from relationships as they get older? Are we normalising unhealthy relationships? Are we sowing the seeds of the sense of entitlement that some men can feel over women’s bodies?

It also minimises the girls understandable reaction and teaches her that she may not get the support she needs when telling an adult about this sort of thing. By not addressing the violence, as well as sending messages that say that this kind of behaviour is acceptable, we are missing an opportunity talk to boys about healthy ways of expressing and demonstrating their emotions and showing respect to other children.

How do these messages develop as children get older?

A piece of research conducted by Dr Nancy Lombard from Glasgow Caledonian University demonstrates how as children get older some of these messages have begun to take hold. She spoke with groups of 11 and 12 year old children in Glasgow about their ideas about violence and what she found was very worrying. In general, the children saw violence as just part of being a man – it was natural that men (and boys) were violent. We know that this is not the case. Boys are not naturally more violent than girls. Male violence and aggression is very much a direct result of the gender boxes we spoke about earlier.

The children also had a very fixed idea of what constituted “real” violence – a serious physical act, committed by adult men, in a public space resulting in an intervention. They did not see the kind of interpersonal relationship violence that many of them were experiencing as real violence. This was partly because it didn’t fit with their definition of violence, perhaps not a physical act, and because it was often minimised or unpoliced by adults. Girls felt like their reports to teachers for example were not acted upon.

What can happen next we see in some of the statistics around interpersonal relationship violence between young people, and then the continued issues of men’s violence within the home.

An Equitable and Intersectional Approach

One of the most important things we can do is to provide a counter narrative. The world is a gendered place – the stereotypes are everywhere – by the time the are 3 or 4 children will have absorbed so many of them. Treating every child exactly the same will not work – we need to recognise the barriers facing different groups of children and give them the support they need to overcome them. We need equitable approaches, where everyone gets what they need to help them fully participate and overcome the barriers that they face if we want to reach a state of equality of access and opportunity.

So for example we know the world in all sorts of ways sends a message to boys that they need to be emotionally strong. The whole “boys don’t cry thing”. So we need to provide a new narrative. How can we make sure boys are exposed to caring emotionally vulnerable male role models. How can we specifically encourage emotional literacy in boys? This is equity.

As well as considering things through a gender lens, it is vital that we consider other power inequalities and discrimination which mean that some children may face additional barriers. Things such as race, ethnicity, social class and disability for example. We need intersectional approaches which mean that no child is limited, discriminated against, or unable to participate, achieve and thrive.

For more info on Nancy’s research see:

Because they’re a couple she should do what he says’: Young people’s justifications of violence: heterosexuality, gender and adulthood

Lombard, N., 3 May 2016, In: Journal of Gender Studies. 25, 3, p. 241-253 13 p.